Getting to here

A friend and colleague suggested writing the story of my working history to understand how I got to this point. I found it an interesting exercise that helped me clarify my thinking. Most of it will not be relevant to many readers, but it is here for anyone who has an interest.

Background

The Old World

Moving to Auckland in 1990, I applied for a job at Colmar Brunton, a Market Research company. The role turned out to be as a trainee under Dr. Hester Cooper in the Sensory Evaluation team. She had commercialised an impressive process; by creating a standardised environment and more sensitive questions in a self-completion questionnaire, she needed fewer respondents and staff yet produced richer insights. It had recently allowed Colmar Brunton to open a successful Sydney office under dynamic young management. It was an exciting place.

Over the years, I moved from Sensory into the quantitative team, learning to write questionnaires that would be read out to respondents rather than completed by them. Later, I joined the qualitative team, learning in-depth and focus-group interviewing methods. I moved overseas and learned how things worked in different countries and companies. I loved almost all of it. I hardly ever had to go outside, there was lots of sitting, it was all about people, and it was fascinating and fast-moving. We turned projects around in weeks — design, fieldwork, data entry, analysis, reporting, and recommendations. We worked on several projects at once, often late at night or on weekends. It’s expected that executives work beyond normal working hours. People usually learn a lot and become increasingly well paid, but it interferes with personal lives. Sacrifices are made that should not be necessary, and go largely unappreciated.

Back then Market Research Companies had their own fieldwork teams, which were large and nationwide. Interviewers would go door to door, or intercept people on the street or in shopping malls. CATI (Computer-Aided Telephone Interviewing) interviewers sat in cubicles, phoning people randomly selected from the telephone books that listed nearly everyone, even Sir Edmund Hillary and Colin Meads. It was part-time, flexible work, done mostly by women as a supplementary income to earn their own money. Much of that work has disappeared, along with the manual coding and data entry of paper questionnaires. We can regret the loss, but those jobs were hard and too often tedious. Interviewers needed excellent social and organisational skills yet were not well paid. It was notoriously difficult to get the people who designed the surveys to go door to door or get on the phones, and do some actual interviewing themselves — myself included.

The New World

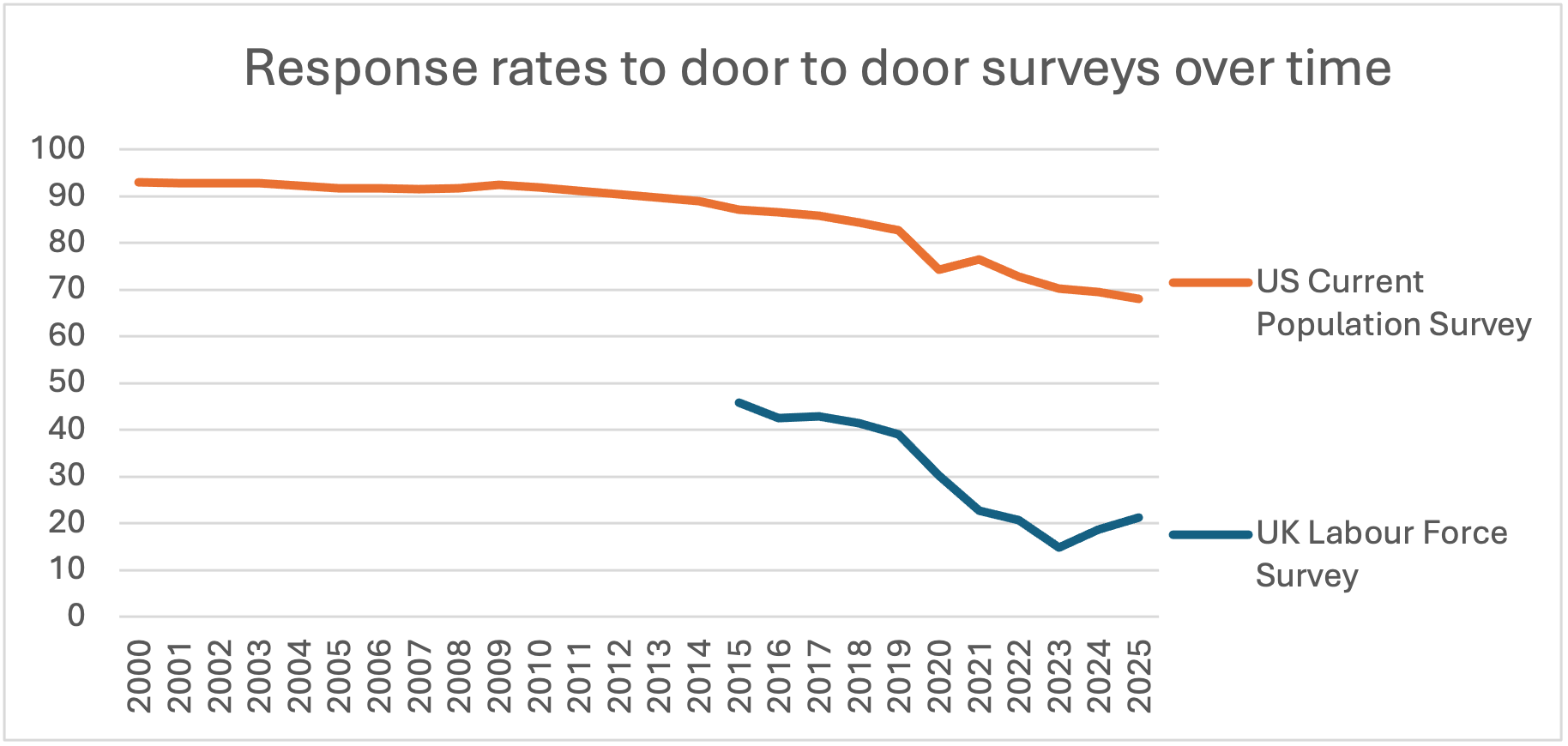

Online self-completion questionnaires have democratised access to survey-based research, making this technique available to more people and organisations. But my favourite part, is that we no longer have to interrupt people during dinner. It used to irritate my mother and she is not alone. Knocking on someone’s door or calling them out of the blue is increasingly seen as intrusive. Response rates for face-to-face interviewing have dropped sharply over time.

These days we can let people respond at a time that suits them. While the government collecting the census or important national surveys interrupting your dinner can be framed as accepting your civic duty, when asking people about their behaviours as consumers, we are relying on their goodwill, and therefore good manners matter.

Recently, AI started taking out the grunt work out of analysis and reporting. Coding of open-ended questions into themes that once took days now takes minutes and the standard is high. Boring hours of data cleaning and making tables and charts is automated. The AI interpretation of tables and charts is currently naïve but will only improve. This is the second factor driving democratisation of access to survey-based research.

Survey-based research has been around for hundreds of years but was only affordable to states and

the biggest organisations. Now, between online interviewing and AI analysis, all that has changed.

Implications of these Changes

We cannot claim to collect a random sample

When we called/visited a random sample of households multiple times to find people who were not home, and response rates were 90% or more (thanks to the persistence and social skills of interviewers), that claim was plausible. We don’t get anything like that from online channels. An email to an engaged audience might yield a 10–30% click-through rate — but often much less. Social-media advertising can produce single-digit or even sub-1% clicks vs. impressions.

Does it matter? If it’s not a random sample, we can’t confidently project findings back to the wider population. Samples are skewed by demographics. You should compare your sample demographics against census figures to understand the differences. One way to adjust is by weighting the data. Usually, more women respond than men, so you can weight women’s responses to less than 1, and men’s to more than 1, and achieve a 50/50 representation of male and female views in your output statistic. But unless it’s a tracking study or you are trying to predict an election, weighting is not my first choice. It feels disrespectful to down-weight people who took the time to help. First, we examine responses by demographics to understand what differences exist. Depending on the topic, they can be trivial or substantial. Once we know that, we can make a more informed decision on weighting.

How different will my sample be vs. my total audience?

Many studies have explored this question, and the evidence shows that with caveats (discussed below), the proportion of your audience who complete a survey (for example, 0.1% or 30% or 80%) doesn’t change the findings much. Your charts will usually look pretty much the same. The rankings of responses will likely stay in the same or similar order, though may not be the same magnitude. Every one of us is a unique individual, but we respond to communications and environments in similar ways.

The caveats to this are how it is distributed and what is influencing the audience. A high response rate to a poll you shared to your followers on X will be far more skewed than low response rates from a more diverse set of channels and influencers. Also, if there is a correlation between an opinion you are trying to measure and someone’s likelihood to take part in your survey, there will be an impact. An example of this is highly motivated customers (either positively or negatively) are more likely to complete customer feedback forms.

What’s the answer?

Firstly, reach out through multiple channels. Your social media, email lists, flyers, influencers, Google ads, peer to peer, traditional media, letters in the mail, pen and paper, kiosks, in person interviewers, personal invitations, whatever you can afford to access and is appropriate for your audience. To get outside your marketing bubble, there are companies that provide vetted panellists of incentivised respondents. It can be useful to track each channel and compare the results from different sources.

Secondly, create thoughtful communications that respectfully invite your audience to take part in a way that is convenient to them, and explains the benefits of doing so.

High CPI —> Low to Zero CPI

Interviewer administered surveys came with a high CPI (cost per interview). One effect of this was that we would either totally exclude, or have maximum quotas for people over 65. If we didn’t, our samples would over represent this age group because older people are easier to find at home and have more time.

Online interviewing means we don’t have to consider CPI to the same extent and can appreciate input from everyone – cutting it up at the analysis stage to understand differences.

This has led to the opposite problem → people are receiving too many survey requests. With online research through your marketing channels and AI to help with analysis, the additional cost of adding more interviews is (mostly) borne by the respondent.

This puts us in the position of kaitiaki/guardians of their time and gives us the responsibility not to waste it with poorly designed surveys or asking them for information that will not be put to good use in your organisation for their ultimate benefit.

Fieldwork requires a communications plan

Now that we cannot rely on interviewers for recruitment, we need to think about why your audience would take part in your survey.

The biggest influencer is you. It mostly depends on who’s asking, where, and how, i.e., on your relationship with them and your communications to them about it.

Then there’s pro-social bias — people want to be helpful. Some people enjoy having a say. Some have a beef with you, or want to give a compliment. Some are bored. Some nosey. Some dutiful. More than one motivation may be involved.

Incentives help. They can nudge participation in your favour. Providing an incentive is good manners — utu/reciprocity for someone’s time and attention. Incentives reflect your brand and need to be desirable to your audience, but not so desirable that they attract bots or their human equivalents.

A downside of moving from person-to-person to online we often do not sufficiently consider, is that we exclude people who are not online or who have low literacy. Disability can also prevent participation. Survey designers need to understand how questionnaires will work with assistive technology and on older phones. Communication plans need to consider a variety of options so that anyone can take part.

Thinking about this helps you to create a communication plan which will make your online survey more successful.

An increased centrality on the respondent experience

In person-to-person interviewing, the interviewer has the hardest job. So we design the survey tools (questionnaires, showcards, contact sheets) to make it easier for them. In online surveys, the hard work is being done by the respondent, all by themselves.

As you will recall from your own experiences with taking surveys, respondents do not apply the care of a forensic chemist to the task. People skim. They satisfice (= satisfy + suffice) — giving a “good enough” answer rather than a perfectly accurate one. They offer more socially acceptable responses than they may truly feel or practise IRL. We write and interpret questionnaires with this in mind, planning for and managing them.

Respondents deserve as seamless and streamlined an experience as possible while still meeting all your information needs and their desire to communicate to you. Questionnaires should be made as simple as possible — but no simpler.

An unchanged need for expertise

The need for expertise in survey design has not changed. Questionnaires are a communication tool, a scripted conversation between an organisation and its audiences. A conversation that will be repeated dozens, hundreds, or maybe thousands of times, mostly inside people’s heads. They require thoughtful, expert co-creation between people who understand the audience and what they want to learn from them, and someone who understands what they are doing in survey design.

And here we are

Given the point we are at, I am launching two services.

When I was a child in the 1970s, I used to surprise and amuse people by telling them that I wanted to be a scientist when I grew up. It was still unusual for a girl back then. But I loved Science and Maths, and also English and learning about people through long hours spent inside reading books.

As I got older and started making real career decisions, I realised that my job needed to suit me — an asthmatic, shortsighted, easily exhausted, sociable, weak-stomached, indoorsy sort of person. The only scientist jobs I knew of at that time were in the Crown Research Institutes for Forestry and Agriculture which did not sound promising. While studying for my degree, I became fascinated with the digestion and fermentation that happens in the large colon. Realising what the laboratory work would involve ended that idea. After university, I worked in two laboratories — at FRI (now Scion) and in a dairy factory. The dairy factory was a lot like working in a kitchen. There were recipes followed by dishes and I hardly ever got to sit down. FRI was more me. Cool equipment, interesting people, and the environment was scholarly and unhurried. But experiments could go on for years, sometimes decades, and were inevitably about wood.

To me, it seemed like we hardly ever found anything out, and when we did, it wasn’t particularly interesting.

The Event Measurement Company

Coming February 2026

Great events create memories and bind communities together. There is increasing interest in providing events and in improving them. They can attract funding from charities and local governments that require proof of success. This requires research with event participants.

Event size scales in orders of magnitude. There are in-person events for dozens to tens of millions. Online events reach billions. Their budgets follow a similar scale. The cost of researching them needs to encompass a much wider range.

Through the “great democratisation” of access to survey research, we are planning to provide a customised survey and report for a community event for as little as $300, a fuller exploration of a larger data set for around $1000, and a product with advanced analysis for larger or commercial events, from $3,000 to $20,000.

We are focused on integrating more AI and automation to keep these costs low or further reduce them over time. But human minds will always be involved in the interpretation and in quality assurance.

FC Research

This is my bespoke survey research company. It is important to continue to learn and be involved in a wide range of organisations and topics. I am offering clients who have an audience they wish to survey, a customised design and analysis service.